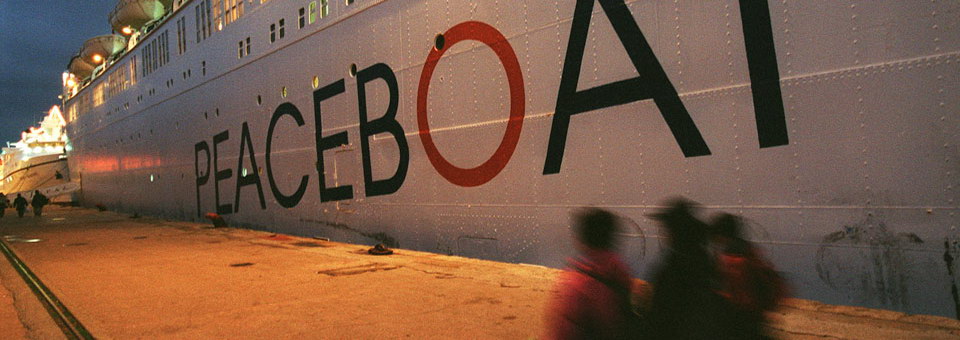

Peace Boat – Freedom on Sea

by Michael Gleich

by Michael Gleich

Photos: Uli Reinhardt

Japanese activists founded a peace university that constantly circles the globe.

The ship devours its passengers one after another. It digests them in its 150,000-ton hull. It ferments them in the brine of seven seas. And it spits them out three months later, once they’ve ridden the waves around the world, alive but fully transformed.

After only 30 days at sea, somewhere between the Egyptian Port of Suez and the Greek harbor of Piraeus, the Chinese Jingjing, 22, begins to show the first symptoms of metamorphosis. She is utterly confused. Many of her sentences begin with “I don’t know.” She left her native country for the first time in her life to board the Peace Boat in Tokyo. Since then she has visited the archenemy Taiwan, the unknown neighbor Vietnam, Singapore “where everything was shop-until-you-drop,” and Eritrea, “where the poor are even poorer than in rural China.” Every shore leave is an excursion into culture shock, and on board she is faced with 981 Japanese, whose customs cause her additional alienation.

The coordinates by which Jingjing used to orient herself seem to have lost their validity. Taking a stand in China is the party’s job. The student Jingjing may have criticized this in the past, but she never really doubted its foundations. And now? “I don’t know,” she says. “When I get back to Beijing, I’ll have to take a closer look at a few things.” The functionaries claim, for example, that almost every Taiwanese longs to return home to the Middle Kingdom, but her contemporary on the ship, Tarko from Taipeh, tells a different story. According to him, everyone but a few nostalgia-addicts argues for the island’s continued independence. Where does the truth lie?

On the open ocean, unquestioned certainties begin to waver. That is the stated intention of these alternative cruises. They have been organized for over 20 years by the Japanese volunteer organization Peace Boat. With nine decks, its 200-meter steamship offers all the comforts of a commercial ocean liner. What is unusual is the choice of ports –harbors like that of Massawa in the developing country Eritrea, there to assist with the reconstruction of a school, or a stop to collect computers in Japan for distribution in the slums of Rio de Janeiro.

During such excursions and on-board lectures, around 1,000 passengers learn that there is more to discover beyond the horizon than Disneyland and the Hofbräuhaus. There is the entire diversity of life, with its conflicts, poverty, and underdevelopment. Peace Boat passengers do not swarm over the usual sights with eyes fixed on their cameras. Instead they cautiously explore cultural features, local issues, and creative solutions. The research ship sails the globe at 21 knots, a “discovery of slowness” driven by a 21,000 horsepower diesel engine and the optimistic credo “Peace is possible!”

There are four other “international students” on board besides Jingjing and Tarko: the Israeli Itay, the Palestinian Iba, the American Tyler, and the South Korean Narae, all in their early 20s. The program uses scholarships to recruit young people from conflict zones (yes, the U.S. makes the list). The theme of today’s group discussion is truly universal: men, women, and the eternal battle of the sexes. Everyone has something to say. “In my grandfather’s house, only men sit down at the table. The women work in the kitchen and serve the food,” says Jingjing. Israel is the world leader when it comes to trafficking in workers, claims Itay. Iba says that Palestinian men hold their wives’ hands in the delivery room. Her mother is a feminist, says the South Korean Narae, but without a husband and children “she would have felt like a loser.” Tyler offers a curious tale from a Midwestern agricultural fair. Women were polled as to whether they supported giving women the vote. And – “crazy!” – 80 percent were in favor, although women have voted in the U.S. for 100 years. The group laughs a lot, a relaxed intercultural dialogue. All sit barefoot on bast mats. The walls tremble in rhythm with the ship’s engines. Japanese boys are on deck playing soccer. Only Jingjing seems to get more and more insecure.

“The party says men and women have equal rights.” Why, then, are all the top functionaries male? She sinks her head, hiding behind a curtain of shoulder-length hair. Her lips are pressed together. “I don’t know.” The power of propaganda, at home inescapable, dissolves in the ocean mist. A vacuum takes its place, and Jingjing knows it is up to her to start thinking and fill it up again. The inner journey, as so often in life, is more eventful that the outer one.

On the ship as sanctuary, plowing through in neutral waters, declared enemies can speak openly with each other in a way that is difficult in the poisonous atmosphere of their home countries. Israelis meet Palestinians, Indians confer with Pakistanis, Tamils meet Singhalese for the first time, Colombian rebels talk to government supporters. The hosts take conscious advantage of their position. The open sea encourages open dialogue. Outside the 12-mile zone, tongues are loosened. Unlike at a typical conference, there is no escape. No matter how hairy the discussions get, the parties are sure to meet again in the small world of the ship. That encourages fairness.

Jingjing’s father died four days before the ship put to sea. Her mother and two siblings were left with no one to support them. But she didn’t cancel. “This trip is the chance of a lifetime,” she says softly, her voice shaking a bit. Her mother pressured her not to let the ticket expire. She would make ends meet by baking and selling bread in Beijing. When the “international student” discussions turn to the big global themes of democracy, human rights, and nonviolence, Jingjing can seem absent. She thinks of home. Will the university be beyond her reach? Will she have to give up her studies of English and political science? Her dream of one day becoming mayor of her home town, “because somebody has to replace the corrupt, ruthless cadre that’s in power now,” recedes into the distance. At times she just starts to cry.

The other students comfort her. Even those from wealthy countries have begun to understand what everyday poverty means. In Sri Lanka they and the Peace Boat delegation visited a village that had been rebuilt by refugees. Tyler, studying communications in Minneapolis, felt the difference viscerally “between whether you’re being offered war and refugees on TV as consumer goods, or you’re in the middle of it, seeing all the horror with your own eyes. When you feel it, touch it, hear it, and smell it.” The students meet a family that has collected, cleaned, and neatly flattened candy wrappers. Glued to the interior of their shack, the wrappers substitute for wallpaper. The invincibility of the longing for beauty, even in the midst of misery, deeply impressed the students. Since then the refugees are a constant presence in their discussions.

A unique financial arrangement keeps the Peace Boat afloat. It admits passengers more interested in tourism than peace, taking them around the world for $10,000-$15,000. Their tickets sponsor the journeys of the volunteers who study on board while organizing protests and humanitarian help on shore. The secret deal reads: The activists spread the word, and the tourists fill the boat. But sometimes the enthusiasm is contagious. Educational offerings are open to all. Lectures with titles like “The True Reasons for the War in Iraq” or “Fair Trade” can draw crowds of several hundred even late at night. “ Japanese don’t travel to relax. They want to learn,” says Jasna Bastic, one of the organization’s few full-time employees. For the 45-year-old Bosnian, every tourist who shows curiosity and sensitivity in dealing with his hosts is fulfilling a peace mission. “Especially the Japanese, who traditionally have been isolated on their islands, have an underserved need for real contact with other cultures. Our ship is a medium that gives them that information firsthand.”

The chance can only be enjoyed by the young (not yet employed) and the old (no longer employed) – but they enjoy it with bells on. At six a.m., tai chi on the outer deck. At eight, belly dancing in the Windjammer Bar. At ten, teiko-drumming by the pool. After that, sign language. In the afternoons, karate for women. In the evening, a lecture on “Slow Food.” At midnight, communication with aliens via “pyramid power,” or, alternatively, the ever-popular game of catch-the-alien (with a towel). Or the “Gangsta-Party” in one of the bars. It doesn’t wind down until the last celebrant staggers exhausted to his cabin. Most of the programs are organized by the passengers themselves. The Japanese, a fishing people, discover the liberty of the high seas.

The wiry Mr. Toshi, an author and sword fighter in his early 60s, is one of the younger older people on board. He sees his horizons broadening every day. “We Japanese know too little about the world. Our school textbooks say nothing about what we did to Korea and China in World War II. We have no idea how other countries see us. That’s frightening!” Eritreans eat spaghetti? Italy has active volcanoes? Europeans gets six weeks of vacation a year? His sojourn brings him one exotic insight after another.

It is the “international students” who profit most from the tourist subsidy. Student loans alone will not buy such an exclusive ambience. The students exchange views with contemporaries from distant lands, study the consequences of globalization on location, listen to lecturers from around the world – then jump into the pool. Instead of a student cafeteria, they lounge in dining rooms featuring white tablecloths and waiters in uniform. State College meets the Love Boat. This year will see the first German students on board.

It is their 33rd day at sea when war breaks out. The bare shores of the Peloponnesian Peninsula slowly pale beyond the stern. The sea is calm and deep blue. A good morning, the students think, to have breakfast in the Yacht Club on deck eight. A happy tumult ensues as a school of dolphins is seen on the port side. There is a ritual rush to the railing, and a phalanx of photographers materializes out of nowhere as if at a presidential photo op. The dolphins’ leaps are greeted by an orchestra of greetings and clicking. In the seminar room, the war starts rather harmlessly. The theme is nonviolence. Tyler, the American, is reporting on the achievements of Gandhi and his successors, the American civil rights activists and South African opponents of apartheid. He praises civil disobedience as the ultimate weapon against oppression. The longer he speaks, the more uneasily Iba, the Palestinian, shifts back and forth on her seat.

Finally it bursts out of her: “That stuff is useless!” She requests that the others explain to her how a people controlled, humiliated, and imprisoned by a vastly superior military power “is supposed to defend itself with a bunch of pitiful protest marches.” She condemns suicide attacks that kill Israeli civilians, but not armed attacks on the military. Jingjing: “Violence only creates more violence.” Jasna: “No conflict lasts forever. There are other solutions.” Tyler: “It’s a question of time and resolve.” One by one, they swamp her with helpful suggestions.

The Palestinian lives in the Arab section of Jerusalem. Many relatives are cut off in the West Bank. The more time the others spend proposing peace plans, the more Iba sinks low in her seat, knots her frail body together, and stares at the floor. Eventually she calls out: “You all have no idea. You don’t know what it’s like to live under an occupation. You have no right to talk. And anyway, what do you plan to do for us, Tyler, when you get back to America? And Narae, what about you?” When the South Korean, her best friend on board, replies that she is “totally rude,” she starts to sob and doesn’t say another word. Attack, defense, misunderstanding, escalation, injury – suddenly there it is, her personal conflict, under the flag of the Peace Boat. Didn’t they all participate in the opening ceremonies of the Olympics in Athens? Have they forgotten all the speeches invoking the Olympic peace? Did the ceremony, which symbolically united the Olympic flame with the eternal flames of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, carried deep inside the ship, vanish without leaving a trace?

Negotiations start in the cabins. At first they are internal to the Middle East. Palestine confers with Israel. Iba confides her hurt feelings to Itay: “I came on board to represent my people. I want to tell people what it’s like to live in fear every day, from morning to night. We’ve gotten so used to being afraid of abuse, having our houses destroyed, rocket attacks, that we don’t even feel the fear anymore. It’s a constant companion. Here, on the ship, where I feel safe, the fear comes back. Then it starts to seem really strange to me that I’m here enjoying safety and luxury while people at home are suffering. Our situation is so hopeless. Nobody helps us. Not the Europeans, and certainly not the Americans.” She composes her face and throws her long, dark curls back energetically. “Then along comes Tyler and sings the praises of nonviolence, and the others join in, giving me advice when they’ve never experienced terror for a day in their lives. Just great.”

Itay voices his agreement. What do they know! Outwardly, he is the opposite of the Palestinian. Powerfully built, shaved bald, he wears camouflage pants and jump boots. But since the two came on board in Tokyo, they have been allies. The 20-year-old from Tel Aviv belongs to an anarchist group that regards Israel as a fascist entity and aligns itself regularly with Palestinians. At night they try to sabotage the new separation wall, or help to smuggle the olive harvest into Israel. During the day they offer themselves as human shields to protect Palestinian demonstrators. “There’s no war between Jews and Arabs in the Middle East,” says Itay. “There’s just a war of extermination by those in power against the powerless.”

Why did he board the Peace Boat? No, he wasn’t summoned to further international dialogue. “I needed a vacation,” he says blandly. After an Israeli rubber bullet injured his left eye, he decided to get out of the line of fire. “While I’m here, I can spread the word that not all Israelis are as stubborn as Sharon.” On the ship he leans toward provocation, with his preference for torn shirts and fatigues, or his glib description of the Peace Boat as “a tourist attraction with a peace alibi.” In the conflict among the students, he immediately takes Iba’s side.

The parties discuss the conflict by twos. “Iba feels she was attacked, but she was the one who nailed us to the wall, wanting to know what we can do for Palestine,” says Tyler. Jingjing: “I don’t know how the argument got out of control.” Narae: “In South Korea, baiting people is bad manners.” Iba: “I just asked neutrally who’s just talking, and who actually plans to get involved.” Each asks the others how he could possibly be misunderstood. Taiwan abstains, China pulls strings in the background, and the U.S. seeks an alliance with South Korea while Israel and Palestine form an unexpected Middle East Bloc. It is clear to everyone that a mediator is needed. Can Bosnia help?

Jasna Bastic, the course leader and initiator of the international student program, has seen such crises on board before. “Our motto, ‘Peace is Possible,’ doesn’t mean there’s not going to be conflict.” She teaches the students to analyze causes, patterns, and protagonists to come up with possible solutions. She herself attended the school of hard knocks: born and raised in Sarajevo, trained as a journalist, she fled the Serbian siege to Austria and Switzerland. There she resolved to convey the reasons for the war in her homeland as objectively as possible. She has seen war’s banality, and its extremes. “And I saw how propaganda turns minds into minefields, and poisons souls.” Her destiny makes her a confidant for the students on board. Her well-aimed questions stem from a deep understanding. Her tomboyish gentleness makes her something like an older sister, with a license to praise and comfort.

“The ship is a microcosm,” she says, “ a little model of the world we’re circumnavigating.” Now, while it’s every man for himself, her diplomatic abilities are called upon. The Bosnian announces a summit meeting. They all get the time they need to explain what they said, what they meant, and what they understood. Arab passion gets the same platform as Korean coolness, American directness, and Itay’s anarchistic Sturm und Drang. “If the Palestinians go on believing they’ll always be victims, nothing will ever change,” says Tyler. “If you think I’ll ever be resigned to what’s happening, you’re wrong. I’ll never give up, never,” says Iba. Outside the sea is flat and calm. Inside, a storm is raging.

Researchers have determined that a civil war lasts on average seven years. The gale in the seminar lets up after only a few hours. Narae confesses to Iba that she made a mistake. “What I thought was rudeness was actually your fighting spirit, and I admire it very much.” On the open sea, it’s easier to get down to brass tacks. A small ceremony follows on deck nine. The misunderstandings are wrapped in little packages and dropped overboard. Peace? Peace. For the time being. Each of them has discovered unknown aspects of the others. It’s like with the ocean: the greatest danger is not on the surface.